Siding

Siding

What evidence have people come up with since the time of Cecil Sharp that into-line siding was the correct interpretation?

People get very dogmatic about these things, and usually they're at their most dogmatic when they don't have a leg to stand on. When I started calling in 1978 virtually everybody did “Cecil Sharp” siding — left shoulder over, right shoulder back. I've known cries of “rubbish” when I called a dance using into-line siding and said that I believed this was what siding really was. When they said “rubbish”, what they meant was that they'd been doing siding the Sharp way for forty years, and how dare a young whippersnapper suggest that they'd been doing it wrong! But Sharp himself wasn't dogmatic — it was his followers who put him on a pedestal. How many of people who thought they knew it all had actually read what Sharp said in the Country Dance Book in 1911?

Although I have consulted all the sources of inspiration at my disposal, I have been unable to find any authoritative definition of this figure… Some solution had, therefore to be made. (Part 2, page 19.)In other words — I made this up, and it seems to work. And in Part 6 — his final thoughts on the matter, published in 1922:

Further evidence which has come to light with respect to this troublesome figure seems to throw doubt upon the accuracy of the half-turn in each portion of the figure, in the form in which I reconstructed it. Now if, instead of turning, the dancers were to “fall back to places” along their own tracks, the Side would then be identical with the Morris figure of Half-hands, or Half-gip. And this, I suspect, may prove to be the correct interpretation; but until it is supported by far more definite and conclusive evidence than we at present have, it would, I think, be unwise to make any alteration in the figure as it is now executed. (Part 6, pages 10-11.)This is Cecil Sharp saying in print that into-line siding may prove to be correct. Tom Cook told me that Maud Karpeles was mainly responsible for part 6 of the Country Dance Book, and she introduced many rigidities in the 1920's; Sharp actually wanted to replace his own version of siding by siding into-line, but she and other followers would not allow it. Mike Barraclough says that in a lecture to teachers in Aldeburgh in 1923 Sharp made it clear that he was convinced but the English Folk Dance Society was unwilling to have the interpretation changed.

Here's an interesting quote from Sir Richard Runciman Terry. A. H. Fox Strangeways asked him for information about Sharp for the biography he was writing, and in his reply Terry said:

He started off all right in the folk song business, but when he found himself in the position of High Priest of a cult he succumbed to the necessity of becoming an oracle. He invested (or rather enveloped) the simplest things with that halo of mystery that so fascinates female devotees. He was neither a folk-lorist nor an anthropologist, but he had to keep up the pose of being both. Once having formulated a theory it became a dogma with his following, and he was more or less forced into the position of having to make his folk-song 'facts' fit his folk-lore theories.Terry is talking about song rather than dance (he was Director of Music at Westminster Cathedral) but I imagine it was true of dance interpretations as well. Note the phrases “the necessity”, “more or less forced” — it really wasn't Sharp's choice.

And there were times when it must have been obvious to Sharp that he had got it wrong. His bizarre “half-siding” in Nonesuch is one example. See my book Playford with a Difference for Mike Barraclough's version which makes so much more sense. Another is in Ay Me, or The Symphony where Playford says,

Sides all into each others places, back men, back We. turn S. . This againe :

I would interpret this as moving into line right shoulder to right, then continuing into partner's place. Then (as in the other two figures) men step back, women step back, all turn single. But Sharp interprets it in the Country Dance Book part 4 as:

Partners honour (2 bars) and change places, passing by the left (2 bars)…

Whereas for the last figure Armes as you sided

he has

Partners arm with the right once-and-a-half round, and change places…

One Playford dance which Sharp didn't interpret (and I can't say I blame him) is The Cobbler's Jig which actually says:

The first man sides with his own wo. then on the other side of his own wo.

Or take Parson upon Dorothy where Playford says:

The first man side with his Partner on one side . Then on the other :

Or Joan's Placket where Playford says:

The first couple sides of one side . and on the other side :

So, if the books of the period don't explain what siding means, how can we have any real idea? One answer is that some books didn't use words at all — they used diagrams. The French Dancing Master Raoul Auger Feuillet invented his Feuillet Notation to show the paths of the dancers and various other important points like taking and releasing hands, setting, other special steps and so on. If you find the original Playford notation hard going, you might think that this would be a distinct improvement; in practice I still find it hard work, and you can study a diagram for ages before you decide that it simply means “circle left”!

John Essex published “For the further improvement of dancing” in London in 1710. Here he explained the Feuillet Notation and gave a number of dances, some of which are from Feuillet's French publication, while others are his own compositions. Two years later, Dezais published “Recueil de nouvelle contredances” in Paris. This contains into-line siding in several dances. But, you say, if it doesn't use words how do you know it's meant to be siding? The answer is in one dance which I can trace back to Playford. This is called Les Mariniers and a look at the music will convince you that the tune is the one used by John Playford in 1651 for “Row well ye mariners”. And to me it seems clear that it is recognisably a version of the same dance. See what you think. Here's Playford's original wording:Longwayes for as many as willThese instructions are laid out under the music, making it clear that each of the four paragraphs above related to a two or four bar musical phrase, and the underlined . and : show that the phrases are repeated. Then Playford prints a line across the page and below it the following paragraph, not tied up with the music at all:Leade up a D. forward and back . That againe :

First man two slippes crosse the roome one way, the Wo. the other . Back againe to your places :

Fall back both . Meet againe :

Clap both your owne hands, then clap each others right hands against one anothers, clap both your owne hands againe, then clap left hands, then clap both hands againe, then clap your brests, then meet both your hands against one anothers . The same againe only clap left hands first :

First man sides with the next Wo. and his Wo. with the next man, doing the like till you come to you owne places, the rest following and doing the same.So what do we make of it? It appears to be a two-figure dance. Since the first starts with Up a double and back, and the second starts with siding, we might wonder whether it's a three-figure dance whose third figure has gone missing! It's longways for as many as will, rather than a set dance, but in fact there are a number of longways progressive dances in the first edition with the three “Playford” introductions so this is still a possibility. Further study of the first figure reveals that there is no progression (unless an instruction that seems perfectly clear actually means something different), so maybe it's one of those dances like Never Love Thee More which has an introduction done once and a progressive figure done any number of times. The second figure is certainly talking progressive — but if it means that we repeat the first figure, substituting siding for Up a double and back, it's equally non-progressive. If we can only discover the progression the whole thing will make sense. Everyone does Up a double and back twice. The top couple do the first figure and progress somehow — i.e. change places with each other. They are now improper, so they can indeed start the next turn of the second figure by siding with their opposite sex neighbour, and so on. But where is the progression?

The next question, of course, is “What did Cecil Sharp make of it?” He makes the first figure non-progressive, and suggests “It will probably be found more effective to omit the First Part altogether.” The second figure starts:

| A | 1 - 4 | First and second men side; while first and second women do the same (r.s.). |

| 5 - 8 | First and second go a single to the right and honour, and then change places, passing by the left; while first and second women do the same (progressive). |

If your version of The Country Dance Book part 3 doesn't read like this, see the list of corrections in the back. By the way, “r.s.” means “running step”, not “right shoulder”.

He then reuses all the moves from the first figure following the “Up a double” introduction but with both couples doing the moves — clearly what Playford gives is only the first part of the figure so this seems a reasonable assumption.

However, the progression is Sharp's fabrication, and also misses the point that in a genuine Playford dance siding always occurs twice. This is much more obvious when you get used to into-line siding; as soon as you side right shoulders you expect the second half. Similarly, I bet you don't know any genuine Playford dance which has a third figure introduction of Arm Right without an Arm Left.

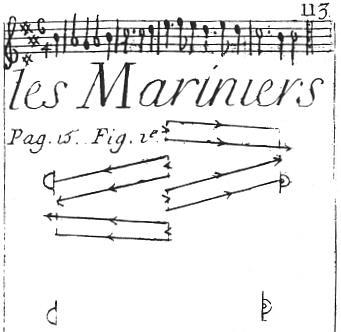

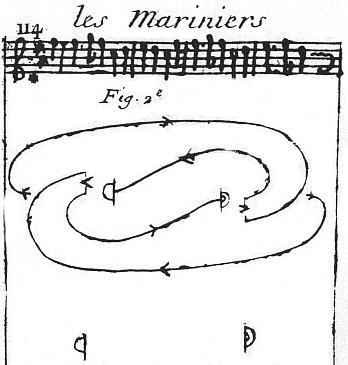

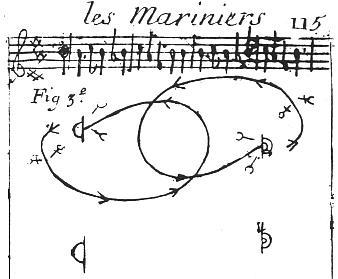

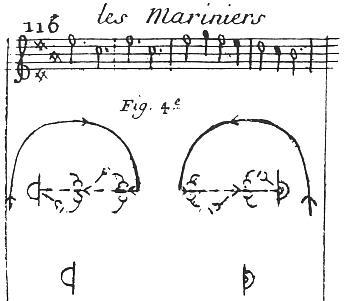

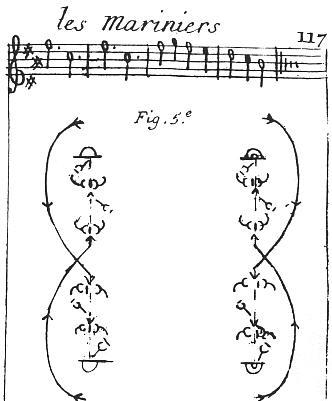

I'm not saying that I know the real meaning of Playford's instructions (which may well contain mistakes), but now look at the Dezais diagrams. I have cut off the bottoms of the pages (which show other couples doing nothing) to save space. The single semicircle is the starting position of a man; double is a woman. Solid lines show the path the dancers move in — and the little marks like arrows are “feet marks” and represent which way the person is facing, so they are the other way round from what you might expect. A broken line means that the dancer's position does not change: it's just there so that you don't have symbols written on top of each other.

I've now done an interpretation of the Dezais version (though it's hardly necessary) at Les Mariniers.

So, the first diagram shows the man moving forward and slightly to the left — facing the same way all the time — and falling back to place, then doing the same to the right. The woman does the same. The movement is unquestionably what people refer to as into-line siding — whatever Dezais may have called it. And the feet marks show that each side is 4 bars, so the 4-bar music needs to be repeated.

The second diagram shows the man moving forward and slightly left, then curving right to finish in his partner's place facing back to where he came from. Then he retraces his steps, curving left back to place. Again the lady does the same. Ironically this appears to be a diagram of Cecil Sharp siding — except that it's the wrong shoulder! I would describe it as a gipsy right half-way followed by a gipsy left half-way.

In the third diagram the little symbols indicate giving hands at the start of the movement and (with the line across) releasing hands at the end. It's a conventional two-hand turn — and it's nice to know that we do a two-hand turn in the same clockwise direction as Dezais!

The fourth diagram has hand symbols with a line in front of them, which means clapping. You can see which hands are used by seeing which side of the track they are drawn on. The sequence is: clap right with partner, together, left with partner, together, then turn single up and out to finish facing the (possibly bored) twos.

The fifth diagram shows neighbours clapping in the same way. And then we get the progression — the ones moving down and the twos up. It's not obvious which shoulder they pass — the diagram rather implies that they walk through each other — but they certainly end up in progressed places.

Now let's compare the three versions. Dezais seems to have taken Sharp's advice about leaving out the introductory figure, and I maintain that all versions start with siding. Notice that Playford says “First man sides with the next Wo. and his Wo. with the next man”, whereas Sharp has people siding with their own sex. Dezais has just the ones siding. These days we would say “Why can't the twos do it as well?”, but in those days the twos only moved in order to help the ones.

The B parts are completely different. Playford and Sharp have people slipping across and back, then falling back and coming forward. Dezais has the two half-gipsies and the two-hand turn. No doubt dances got changed through the “Folk Process” even then; people forgot part of a dance and made something up, or decided that a change would be beneficial.

In the C part, Playford and Sharp use a four-bar clapping sequence repeated. Dezais uses a two-bar sequence repeated, which gives him time for a progression. In fact the music fits Dezais' version perfectly, with the four long notes for the four claps and the shorter notes for the turn single or the progression. Despite the differences, there are enough similarities to convince me that the Dezais dance is derived from the Playford dance.

One interesting observation: in 1735 Walsh published his “Caledonian Country Dances, Volume 1” containing Meillionen, which is word-for-word the same as Playford's 1651 version of “Row well ye mariners”, though with a different tune (of a different length)!

imslp.org/wiki/Caledonian_

There may be people who know more than me about siding, but even if I haven't convinced you I hope I've made you think. Don't believe everything callers and dance teachers tell you!

And there's a postscript. In 2016 John Sweeney was going through old copies of English Dance & Song magazine, to put them on his website and in the February 1941 edition Pat Shaw talks about siding and mentions that at that time people doing “Cecil Sharp” siding did not face each other until the end of each half of the movement, whereas Pat felt that whichever form of siding we use we should look at our partner while moving rather than turning to face at the end. John and I were both surprised that people were doing it that way, but if you look at Sharp's description of “The Side” (Country Dance Book part 6 page 31), you will see that it finishes:

The dancers must remember to face each other at the beginning and close of each movement to pass close to each other, shoulder to shoulder, and always to face in the direction in which they are moving.

That's not the way I learnt siding, and I don't suppose you did either! John's comment was that the movement is “more like a crochet hook than a banana”. A few months later he found a YouTube video (taken from a Kinora Film) which among other dances includes Cecil Sharp dancing “Hey Boys, Up Go We” with George Butterworth, Maud and Helen Karpeles in 1912 — click the picture on the right and you can see what he actually meant. I've started the playback at 3:47 which is when the first siding occurs. What a revelation! I'm not convinced they even glance at each other after they have crossed over, and the men certainly don't glance at the end of the move — they're getting into position for the next move.

That's not the way I learnt siding, and I don't suppose you did either! John's comment was that the movement is “more like a crochet hook than a banana”. A few months later he found a YouTube video (taken from a Kinora Film) which among other dances includes Cecil Sharp dancing “Hey Boys, Up Go We” with George Butterworth, Maud and Helen Karpeles in 1912 — click the picture on the right and you can see what he actually meant. I've started the playback at 3:47 which is when the first siding occurs. What a revelation! I'm not convinced they even glance at each other after they have crossed over, and the men certainly don't glance at the end of the move — they're getting into position for the next move.

So who invented “swirly” siding? Ironically it was Pat Shaw, the man who really started people doing into-line siding! Here's the full text of the article mentioned above, from “English Dance & Song”, February 1941;

A NOTE ON SIDING By PAT SHULDHAM-SHAW THERE has been much discussion on the question of siding in recent years. People have suggested that it should be danced like a half-hands in morris. Others have suggested that it was probably a courtesy movement in which you came up beside your partner and kissed. There is, however, a written description of a movement called Set Sides, presumably the same thing as siding, in a manuscript in the National Library of Wales. In a letter from William Jones to Edward Jones, one of the famous Welsh Bards, the writer mentions some dances that originally came from Shropshire, and conform roughly to the Playford type of Set Dance. The letter is undated, but was probably written about 1790, though the dances are obviously earlier. Before giving the details of the dances, he gives a description of some of the more important movements, including Set Sides. Here is his description of it : “Set Sides: to set to one another always facing, but veering to your left or right or proper or improper.”

I do not know whether Cecil Sharp had access to this manuscript at all, or even knew of its existence. I do know that he arrived at his interpretation of siding after an immense amount of thought on the problem, and his interpretation seems to me to be curiously in accordance with that given above. The only big difference is that the words “left or right” seem to imply that the first half of the figure is done crossing right shoulder, and the second half crossing left, in other words side right and left.

The other difference “always facing” is less obvious, and I suspect was not really a difference in Sharp's original interpretation, but has crept in since. When we side to-day, the majority of us only turn to face our partners after we have crossed over. This means that we are not always facing our partners. If we are going to keep our eyes on them in an affectionate manner without cricking our necks, we must turn as we cross. (This movement is somewhat akin to the “corners cross” movement in The Hole in the Wall as generally danced nowadays.) This movement has a much nicer swing to it, has become a real, movement of courtesy; and in general has far more meaning.

Whether we should now go so far as to side right and left (why not? We arm right and left, and I am convinced that is what happened originally), I have not made up my mind, but I do know that whichever side I go, I get far more satisfaction out of turning as I cross and not after I have crossed.

John's conclusion is:

So, Sharp's original siding was NOT Swirly. As far as we know Sharp never, ever danced a Swirly Siding. However he did believe that Into Line Siding was the correct interpretation. Therefore Into Line Siding is actually Sharp Siding.Shaw was the one, in 1941, who advocated that Sharp's original siding should be danced in a Swirly style with eye-contact. So Swirly Siding is actually Shaw Siding!

That is why I never say Sharp/Shaw Siding, but always Into Line or Swirly.

See also round.

John Sweeney also now has his own Siding page at contrafusion.co.uk/Siding.html.