Interpretations

Interpretations

Links to dances on other pages

Introduction

If you've ever looked at the original Playford notation, or indeed most books of dances from the 17th and 18th century, you'll be aware that they are in need of interpretation (or reconstruction, as people say in the States). The instructions are very condensed, with lots of errors, probably intended as a quick reminder to those who already knew the dances. Playford said “Sides all” and everybody knew what he meant; now we discuss it for hours.Graham Christian objects to “Playford said”, since Playford was just the publisher, and the same is true of Johnson, Thompson, Young, etc. There's no evidence that these people edited or even compiled their books; they just published them. In some cases we do know more: Kynaston was the editor (and possibly the composer); Walsh was the publisher. And certainly if Playford were publishing a book by Purcell I would say “Purcell said”. But we don't know who contributed the dances or edited them; the only name we have is Playford so that's what I use. I could say “The instructions in Playford's book say”, but that seems unnecessarily wordy.

My book Playford with a Difference, Volume 1 contains a number of my interpretations, together with my reasoning behind them. There are dances which I've interpreted since that was published, and I'll be putting most of them on this page rather than publishing a Volume 2. There are also a few where I've done very little in the way of interpretation but still feel it's worthwhile publishing them here.

When I started interpreting dances you had to go to the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library at Cecil Sharp House, the British Library or some other institution. Now you can find various Playford originals online.

- Dancing Master facsimile all Eds. (I prefer to go straight to The Index)

- Playford's Dancing Master: The Compleat Dance Guide Facsimiles plus text and music in modern notation — these may not be accurate and many of the later dances aren't present, but you can check the interpretations against the original wording. However some of the facsimiles (the ones with a yellow background) come from Walsh's Dancing Master of 1709 rather than Playford's — you can't trust anybody!

- Volume 1 Editions 1-10, 12, 14, 17, Part 2 Editions 1, 2, Volume 2 Edition 3 All from the International Music Score Library Project imslp.org

- 1st Ed. facsimile

- 10th Ed. facsimile

- 14th Ed. facsimile

- Vol. 2, 4th Edition facsimile

- 1st Ed. text

- 1st Ed. text and music

You may find the last two easier because they're written in a modern type-face, but they aren't necessarily accurate!

Bob Barrett has found several copies on archive.org. Some may be the same scans as held elsewhere, but archive.org has a better page viewer!

- Second Edition, 1653 This appears to be identical to the Second Edition of 1652.

- ??? Edition Catalogue says 1665, but has no title page and judging from the table of contents it's the third Edition of 1657.

- Fourth Edition, 1670

- Fifth Edition, 1675

- Sixth Edition, 1679 Catalogue says 1679, but actual date is unreadable. Some pages cropped. Dark and smudged.

- Seventh Edition, 1686 Quite dark and smudged.

- Eighth Edition, 1690

- Ninth Edition with Second Part, 1696

- Unknown Edition National Library of Scotland: The Glen Collection. Missing title page and index. “Published : 1697” handwritten on first page. But where does it come from? See below.

- Tenth Edition, 1698

- Second Part, Second Edition, 1698 With handwritten additions to the index. This contains pages 1-16, 27, 18-19, 30-36, then 37 says “An additional sheet to the second part of the Dancing Master” followed by pages 38-48. I make that 37 dances.

- Twelfth Edition, 1703

You can see Bob Keller's lists of the dances in each volume here:

1-1 1-2 1-3 1-3 1-4 1-5 1-6 1-7 1-8 1-9 1-10 1-11 1-12 1-13 1-14 1-15 1-16 1-17 1-18 2-1 2-2 2-3 2-4 3-2

So what is that book from the Glen Collection? It comes from:

digital.nls.uk/special-

I looked through the titles of the first 20 dances of the book and compared them with Bob Keller's database of all the dances in all the editions. There are a lot of dances from the 10th Edition here, plus some from much earlier. But “Up with Aily” doesn't appears until the 12th Edition according to Bob Keller's index, and indeed it's not in the index at the start of the 10th Edition so the Glen Collection must be later than the 12th Edition. I hadn't realised until I began this research that the size of the book jumped dramatically from the 10th Edition of 1698 (215 pages) to the 11th Edition of 1701 (maybe 420 pages though I don't know of a facsimile) — roughly double the size! Why was this? I don't believe there were any competitors publishing country dances at this time, except Thomas Bray in 1699 but his book contained 20 display dances rather than dances for ordinary people. Were lots more good dances suddenly being written? Did Henry decide people would be willing to pay more for a bigger book? I don't know. But I have no reason to doubt Bob Keller's indexes. He says that Editions 13, 14, 15 and 16 start with “Sage Leaf”, “Madge on a Tree” and “Joan Sanderson”, while 17 and 18 start “Sage Leaf”, “Dull Sir John” and “Joan Sanderson”. There are no known editions starting “Sage Leaf”, “Madge on a Tree” and “Ely Minster”. Sorry, I don't know where the Glen version comes from!

You can also find originals of other publishers' books:

- John Walsh: The Compleat Country Dancing-Master or here

- Wilson's Companion to the Ball Room, 1816

- An American Ballroom Companion (Lots of books available here)

- An amazing collection of links and downloads from Nick Enge

- Collections in the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library *

- Links found by George Williams who does lots of animations

- Nick Barber's scans of dance manuals from the British Library

- regencydances.org/sources.php

- …and undoubtedly many others that I haven't yet discovered.

And here's a paper detailing a manuscript which has only recently been studied: Try The Ward Manuscript or direct to the download or if those links don't work you can read about it at academia.edu by signing up for a free account.

If you want to get a quick idea of what dances are in the various editions — particularly an edition not available online — George Williams has various indexes. For instance upadouble.info/index.

Table of Dates

I've been fooled more than once by Bob Keller's layout of the facsimiles in the CDSS website. At the bottom in “Source/Library” he gives the edition from which the image is taken, both edition and year, but that's not necessarily the first appearance of the dance. Three lines up in “Occurrences” he gives all the editions, but no dates. So here's my table for converting edition to year:| Edition — Volume 1 | Year | Publisher | Edition — Volume 2 | Year | Publisher |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-1 | 1651 | John Playford | 2-1 | 1710 | John Young |

| 1-2 | 1652 | 2-2 | 1714 | ||

| 1-3 | 1657 | 2-3 | 1718 | ||

| 1-4 | 1670 | 2-4 | 1728 | ||

| 1-5 | 1675 | Edition — Volume 3 | Year | Publisher | |

| 1-6 | 1679 | 3-1 | 1719 | John Young | |

| 1-7 | 1686 | 3-2 | 1726 | ||

| 1-8 | 1690 | Henry Playford | |||

| 1-9 | 1696 | ||||

| 1-9 Part 2, First edition | 1696 | ||||

| 1-9 Part 2, Second edition | 1698 | ||||

| 1-10 | 1698 | ||||

| 1-11 | 1701 | ||||

| 1-12 | 1703 | ||||

| 1-13 | 1706 | John Young | |||

| 1-14 | 1709 | ||||

| 1-15 | 1713 | ||||

| 1-16 | 1716 | ||||

| 1-17 | 1721 | ||||

| 1-18 | post 1728 |

My Rules for Dance Interpretation

- The dance must fit the music.

- You must know how long standard figures take. It's a common mistake to squash too much dance into a phrase of music. Start by assuming that a cast is 8 steps, not 4. It helps to be able to read music.

- Be aware of the different groups of standard figures, and keep in the style. There's a lot of difference between John Playford (Black Nag, Mage on a Cree, Parsons Farewell) and the Apted book (The Fandango, The Bishop, The Shrewsbury Lasses).

- Be aware that instructions are usually given to the first man or the first couple. In a triple minor, the twos and (particularly) the threes do very little.

- “Cross over” always means “Cross and cast”. (I'm talking about a couple crossing over, not corners crossing.) Read my justification for this further down. Many dance interpreters didn't know this — here are some examples which I have interpreted and there are lots more. “Nampwich Fair”, “Nine Elms”, “The Nobles of Betly”, “Dick's Maggot”. “Draw Cupid Draw”, “Irish Lamentation”, “Jack's Health”, “Mr Beveridge's Maggot”, “The Punch-Bowl”, “Whimbleton House” on this web page, and Portsmouth on my Session 3 page. If you find a counter-example, please Contact me with full details.

- Follow the spirit rather than the letter of the original wording. I realise this is controversial — it gives you the licence to do virtually anything — but I really think this is what makes a good interpretation. Sharp didn't do this — he stuck to the letter whenever possible — and in my opinion that gave him a lot of problems.

Andrew Swaine also has a page on Playford interpretation guidelines.

Andrew Swaine also has a page on Playford interpretation guidelines.

There's also the question of how much you're entitled to modify the dance to suit current preferences. In the 17th and 18th century the progressive longways dances were all about the ones — the twos and threes were just there to help the ones in their passage through the dance. These days, when the shortness of the run means that many people never get to be ones, dancers' attitudes are different.

There's a spectrum of approaches, and I'm very much on the side of historical accuracy, so when I work out what the dance means and realise the twos and threes have nothing worth doing, I usually discard the dance and move on to something else. See my page on Thompson's 1788 collection for examples of this!

Charles Bolton used to say he took the view that the ones' track is sacrosanct but it's permissible to add moves for the other couples. And yet have a look at Lady Winwood's Maggot and follow the link to Charles's version.

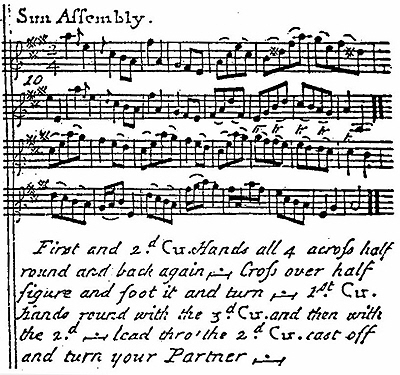

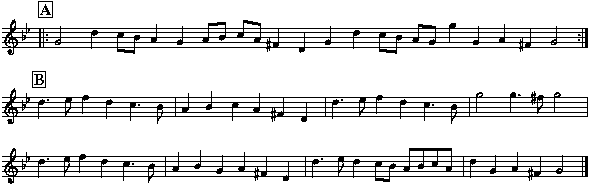

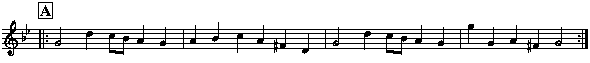

Andrew Shaw also adds things that aren't there in the original, and sometimes changes what is there — you can read about his approach here. And when you get to Tom Cook and Ken Sheffield their dances are often pure invention! For instance, look at the original of Sun Assembly on the right and ask yourself how much of Ken Sheffield's (deservedly popular) version you recognise.

Time signatures

I've never been clear about what the time-signatures in the various Playford editions meant. For instance, the following all have a time-signature of 6/4:Queen's Jig

The Galloping Nag (same dance and tune as Black Nag)

But these are from later editions. When I look at an earlier edition Black Nag there's a circle and the number 3.

And the first edition Merry Merry milke-maids

I don't know what that says.

So I took the sensible step of asking Jeremy Barlow who knows much more about these things that I do. His book “The Complete Country Dance Tunes from Playford's Dancing Master, 1651-c.1728” details all the variations and misprints between the 18 original editions.

He explains:

6/4 means 2 beats or (I suppose) steps per bar, each beat being subdivided into three quarter-notes (American usage) or crotchets (UK), making six of the latter per bar (as in all the examples you've given). So 6/4 means, literally in mathematical terms, 6 x 1/4 notes per bar, but doesn't indicate the way in which the beats are subdivided. The time signatures in early editions are inconsistent, and in the case of Merry Milkmaids a mistake, along with the key signature of one flat.3/2 also has six quarter-notes/crotchets per bar, but they're subdivided into pairs, making three beats of half-notes/minims per bar. So 3/2 means, literally, 3 x 1/2 notes per bar. An early example with dance instructions in Playford is Old Simon the King (supplement to 6th ed. 1679; 233 in my ed.). It's the characteristic metre of the early hornpipe, e.g. Eaglesfield's New Hornpipe from supplement to the 9th ed. 1696, 353 in my ed.

6/8 gradually replaces 6/4 in the 18th century, as part of general notational inflation. It means, literally, 6 x 1/8 notes per bar. On a quick look through, the earliest example in my Playford ed. is The Pilgrim from the 11th ed., 1701 (462 in my ed.). In its early use 6/8 may sometimes indicate a faster 2-in-a-bar than 6/4. 6/4 and 6/8 are used for many jigs; 9/4 and 9/8 (three beats per bar, subdivided into three quarter-notes or eighth-notes per bar) are used for slip jigs.

The circle is a symbol of perfection, i.e. the Trinity, and in a time signature came to indicate that, for a main beat of 2-in-a-bar, each beat is subdivided into 3, as in The Black Nag (I had to go to an encyclopedia to check on this!). It came to be replaced by 6/4 and then 6/8. The circle was becoming obsolete by Playford's time and the three that follows it is meaningless or redundant. The half-circle or C time signature represents imperfection and means that the main beat is subdivided into 2, as in for example Newcastle. That time signature of course survives.

Cross over

I've been asked to justify my assertion that “Cross over” always means “Cross and cast”. Take a look at the start of “The Collier's Daughter”.The first Couple cross over and turn in the second Couple's Place . And then cross over and turn in the third Couple's Place :

There's no mention of casting, but they must get to the next place somehow — either by casting round the other couple or by crossing through them — and I think in the latter case the instructions would have said so.

Or look at “St Albans”. It seems clear that the first half of the figure leaves people where they started. For the B-music we have:

Then cross over and Figure, the 2. Man lead to the wall, and back again, the 2 Wo. do the same at the same time, then all Hands quite round :

Assuming that “2. Man” is a misprint for “2. Men”, the leading out and back and the circle left do not involve any change of position. “Figure” means “Figure of eight” or “Half figure of eight” and in this case it must be a half figure to get the ones back on their own side. So “Cross over” must be the progressive move, which therefore means “cross and cast”.

Or look at “Portsmouth”.

The First Man Hay with the first and second Woman, the first Woman do the same with the first and second Man; then the first Couple cross over and Figure inn; then Right and Left quite round.

The heys in A1 and A2 leave people where they started. “Figure inn” again means a half figure eight, and “Right and Left quite round” also leaves people where they started the move. The only place for a progression is the “cross over”.

Thomas Wilson in “An analysis of country dancing” (1811) gives a diagram showing “Cross over one couple” and “Cross over two couples”.

Nicholas Dukes in “A Concise & Easy Method of Learning the Figuring Part of Country Dances”, published in London in 1752, has a diagram on page 4 of “To cross over and half figure” which shows the ones crossing, looping down below the twos and then doing a half figure eight up through them, finishing in the second couple's place.

Pat Shaw in “Holland as seen in the English Country Dance 1713-1820” (1960) says,

Cross over almost invariably means to cross over a couple, in other words to cross over with your partner and move down outside the next couple into their place.

I also need to mention “cross over below the second [or third] couple” which I believe means exactly the same: cross and cast one place. In my interpretation of The Punch-Bowl I thought it meant “cross down through the twos” but I've now decided Pat Shaw was right and I was wrong! You'll also see this phrase in Arundel Street, Whimbleton House, Charming Maid, The French Ambassador, The New Tambourin, The Midnight Ramble (page 14), The More the Merrier… And if you search village-music-

What does “Quite” mean?

This is a word which can throw dance interpreters because it seems so obvious that no-one would question it. “Right and Left quite round” obviously means four changes, finishing where you started. Only sometimes it doesn't! “All four hands quite round” obviously means circle left all the way. But again, sometimes it doesn't! I came across these examples while reading through Henry Playford's 12th Edition of 1703 and no doubt there are others in other Editions. In these cases “quite round” means “until you get to where you need to be”! Click a title to see a facsimile of the dance.Indian Queen — a dance we all know, and I've never danced a different version. But the final instruction is Right and Left quite round

and we all know it's three changes rather than four.

Epsom Wells — it finishes (with everyone in home positions):

the 1. man change places with the 2. wo. the other doing the like; then all four take hands and go quite round till the 1. cu. comes into their own places, and then the 1. cu. cast off

So it says the circle is quite round but then gives the finishing places which means it's only half-way round.

The Irish Ground says,

First all 4. hands half round, and turn single, then quite round, and turn single

Here “quite round” means “do the other half circle to finish in home places”.

The Ladies Maggot says Right and Left quite round

but then contradicts itself with till the 1. cu. is in the 2. cu. place

so it's three changes, not four.

Cheshire Rounds — says Right and Left quite round

but then contradicts itself by saying into the second couples place

so again it's three changes not four.

Country Farmer says Right and Left quite round

but it must be three changes rather than four to get a progression.

The Happy Meeting apparently has four changes at the end of both B1 (from progressed places) and B2 (from original places), so the second must be only three changes, even though it says “as before”.

It's even possible that when a triple minor such as A School for Scandal, The Rosetta, Trip to Oatelands, Ticonderoga, Who's afraid, The Bishop (all from Thompson's 1788 collection) finishes with hands 6 quite round

it actually means “circle left and right” which I would certainly prefer! I've no evidence for this conjecture, and there are a couple of dances in that collection which omit the word “quite”, but it's an interesting thought.

In fact I've used it ambiguously myself, as I've found by searching for the word on this page, and so do other people. When I say “It's quite possible” I mean “It's very likely”. When I say “It's quite busy” do I mean “It's very busy” or “It's rather busy”? If a man says of a young woman “She's quite innocent” he means “somewhat innocent” whereas if he says of the accused in a trial “She's quite innocent” he means “completely innocent”.

I have run workshops on Dance Interpretation at Festivals and Dance Weeks in England and the States — if you'd like one please Contact me.

See also my notes on Interpreting dance instructions and The Hey. And I've added links to my Session 2 page for callers which also contains some of my interpretations.

You can see George Williams' animations of many of my interpretations at: upadouble.info/

The Dances

Albarony

Source: Dancing Master Vol 3, 2nd Ed, c1726: John Young.Interpretation: Colin Hume, 2021.

Format: Longways triple minor

First cu. cross over and fall between the 2d. and 3d. cu. then turn single; the first Man take Hands with 2d. and 3d. Woman and turn quite round; the first Woman do the same with the 2d. and 3d. Man . Then first Man go round the 2d. Man and fall between the 2d. couple, the first Woman go round the 3d. Woman and fall between the 2d. couple, facing one another; the Man turning the 2d. couple, and the Woman the 3d couple quite round . Then the first Man meet his Partner, then both Ballance twice and turn single, then lead thro' the two Woman . Then both meet as before and Ballance, then turn single and lead thro' the Men and turn :One question that people sometimes ask is “Are there any dances left to be interpreted?” Yes, there are thousands — and most of them aren't worth interpreting! I have a page on Thompson's 1788 collection where you can see this for yourself! I ran a Dance Interpretation workshop for the Friends of Cecil Sharp House in March 2021 and my suggested list of dances included “Newcastle” and “St Margaret's Hill”. The committee asked me: “can we find dances to interpret that are not canonical favorites?” I looked through the Dancing Master index for letter A and found three which nobody has had a serious go at. This is one of them.

Each line of music is 8 bars, and the instructions say “Each strain twice” so that's standard. We assume “Woman” should be “Women” in two places.

Cross and cast normally takes 8 walking steps, so why and when then turn single

? We're going to circle on the side, so the ones need to finish behind the side lines rather than between the second and third couples, and I assume they do a turn single as they get there. I don't have strong feelings about which way the turn single would be. Another possibility is that the ones cross down through the twos (who move up) and then turn single, but as I keep saying, “cross over” always means “cross and cast” so I'm discounting that.

The word “fall” appears three times in the instructions. I don't believe this means “fall back”, just “finish”, as in “Things fall into place”. So the ones cross over, loop over their right shoulder and finish outside that couple, then circle with them, finishing in lines across.

Now the problems start! What does “Ballance twice” mean? I don't think I've seen any reference to a balance in the Dancing Master. I assume “lead thro' the two Woman” is followed by casting round them back to the middle, which will take eight steps, so I can only assume that the ones set moving forward and turn single. That plus the lead and cast is surely B1. They can then repeat the move through the men — but that again finishes with the first man above his partner with no time for “and turn” which gets them into second place proper ready to start the dance again — remember, this is a triple minor.

One possibility is to leave out the second set and turn single. After casting round the women the ones can go straight into the lead through the men and cast. They then have time to meet with a two-hand turn ¾ to their own side, or to convert it to a three couple dance they can turn to the bottom as the threes cast up. Is it right? I don't know, but I'm pretty sure John Young's version is wrong! Don't forget — he was a publisher. He wasn't a Dancing Master or a caller. No doubt he was a dancer — everyone who was anyone danced in those days — but if you ask a dancer to write down the instructions for a dance he thinks he knows, you'll find he doesn't actually know it that well. And of course the Dancing Masters who read his book would play the tune through and think, “No, he doesn't mean that” and they'd teach it so that it did fit the music — they'd have to!

Albarony

Format: 3 couples longways| A1: | Ones cross and cast to middle place but behind the others, turning single as they get there — twos and threes face them and the twos move up. Circle left on the sides, finishing in side lines with the ones improper in the middle. |

| A2: | Ones cross right shoulder and loop right round one person to finish man above the set, woman below. Circle left with this couple, finishing in lines across with the ones in the middle. |

| B1: | Ones set moving forward; turn single. Lead through the women and cast back to the middle. |

| B2: | Lead through the men and cast back to the middle. Two-hand turn ¾ to the bottom as the threes cast up to second place. |

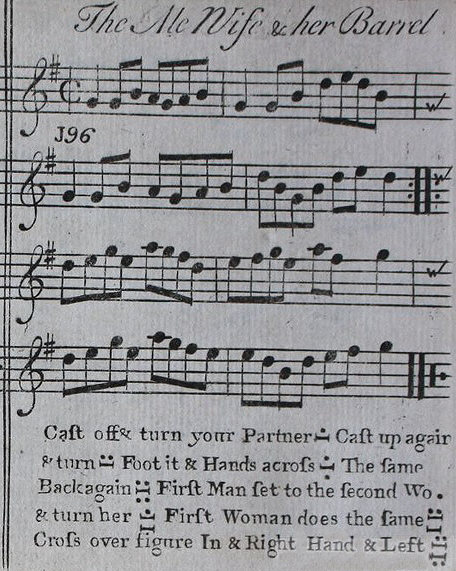

The Ale Wife and her Barrel

Source: Rutherford, 1756Interpretation: Colin Hume, 2023.

Format: Longways duple minor

David Rutherford published it in London, but the dance is claimed by the Scots, so there would be differences of interpretation: a Scottish dancer would expect “turn” to mean a right-hand turn whereas an English dancer would expect a two-hand turn. But the RSCDS version is certainly not what Rutherford wrote. Here's the RSCDS version in English terminology.

| A1: | Ones cast, quick right-hand turn. |

| A2: | Ones cast up, quick left-hand turn. |

| B1: | All set; right-hand star half-way. |

| B2: | All set; left-hand star half-way. |

| A3: | First man and second lady set advancing; right-hand turn — first man end in progressed place. |

| A4: | First lady and second man set advancing; left-hand turn — first lady end in progressed place. |

| B3: | First man cross right with second lady; first lady cross right with second man. |

| B4: | Two changes with hands. |

The trickery in A3 and A4 to get the ones progressed is really awkward. Admittedly the dancers in the RSCDS videos have practiced it long enough to make it look natural, but you can see from Rutherford's original that it's a complete fabrication. And what happened to Cross over figure In

?

George Williams asked me to look at this dance, and once I'd studied the original I saw what the problem was. The A and B music are only 4 bars each rather than the standard 8 so it's all rather frantic. I'm quite sure that “cross over” means “cross and cast” and “figure in” means “half figure eight”, giving an absolutely standard sequence to achieve the progression: Ones cross and cast, twos move up, then ones half figure eight up. But you can't possibly do that in 4 bars. So my conclusion is that the music should be played with 4 beats to the bar rather than 2 — in other words at half the speed of the Scottish version. Click the treble clef symbol and then click “Play MP3” (rather than “Play MIDI”) and see what you think. Now there's time for the stars to go all the way round, time for the “cross, cast, half figure eight up”, time for “foot it” which takes twice as long as “set”… the whole thing falls into place.

George then asked,

Is there any way to tell by looking at the music whether a reel should be played with 2 or 4 beats per bar?If it's 6/8 I know it's 2, and if it's 3/4 or 3/8 I know it's 3, but I don't understand why 4/4 or ¢ or 2/4 is sometimes 2 and sometimes 4…

That's a good question and I don't have a good answer! In addition to the numbers, some composers and publishers use ![]() for 4/4 and

for 4/4 and ![]() for 2/2 — I never do and I always have to look them up! Some composers and publishers (old and new) use 4/4 when in my opinion they should be using 2/2 because there are two beats in a bar, not 4. If you clap or walk to a tune you can normally tell whether it's two or four beats to the bar. Hornpipes and Strathspeys (which are much the same) actually do have 4 beats to the bar, but most reels have 2 beats to the bar. I just believe this one is an exception — it should be notated in 4/4 rather than the C with a vertical line through it which means 2/2. It's quite rare to have a tune where the A and B music are both only 4 bars, particularly when the tune needs to be played through twice for one turn of the dance. So my version of the dance goes like this.

for 2/2 — I never do and I always have to look them up! Some composers and publishers (old and new) use 4/4 when in my opinion they should be using 2/2 because there are two beats in a bar, not 4. If you clap or walk to a tune you can normally tell whether it's two or four beats to the bar. Hornpipes and Strathspeys (which are much the same) actually do have 4 beats to the bar, but most reels have 2 beats to the bar. I just believe this one is an exception — it should be notated in 4/4 rather than the C with a vertical line through it which means 2/2. It's quite rare to have a tune where the A and B music are both only 4 bars, particularly when the tune needs to be played through twice for one turn of the dance. So my version of the dance goes like this.

The Ale Wife and her Barrel

| A1: | Ones wide cast; twos lead up. Ones two-hand turn. |

| A2: | Ones wide cast up; twos lead down. Ones two-hand turn. |

| B1: | All set twice (or fancy step *). Right-hand star (all the way). |

| B2: | All set etc. Left-hand star. |

| A3: | First man set twice to second woman. Two-hand turn. |

| A4: | First woman set twice to second man. Two-hand turn. |

| B3: | Ones cross and cast; twos lead up. Ones half figure eight up. |

| B4: | Four changes with hands. |

* The fancy step (where the original says “foot it” rather than “set”) is described on my 200 Years of American page.

George Williams has provided an excellent animation of this at upadouble.info/dance.

Arundel Street

Source: Dancing Master 9th Edition, 1695: Henry Playford.Interpretation: Colin Hume, 2020.

Format: Longways triple minor Improper

The 1. Man being improper, go back to back with the 2. Man; the 1. Wo. being improper, go back to back with the 2. Wo . The 1. Wo. go back to back, side with the 2. Man, the 1. Man go back to back side with the 2. Wo. then 1. cu. go back to back with their Partners : The 1. cu. cross over below the 2. cu. and go the Figure thro' till they come into the 2. cu. place, then go the Figure thro' the 3. cu till they come into the 2. cu. place, then the Figure thro' the upper cu. and cast off :One of the few improper dances in Playford; a better known one is “King of Poland”. In both cases (and others such as “Arcadia” and “Old Simon the King” in the 7th edition) the printer prints the usual diagram with four proper couples, but the wording is unambiguous.

No difficulties of interpretation here. Arundel Street in London ran south from The Strand to the river Thames until the Embankment was built — it now stops short. That was where John Playford (who was a good musician and singer as well as a music publisher) lived for forty years, and his son Henry lived there until at least 1703. The tune is a rather quirky 32-bar jig.

The 1. cu. cross over below the 2. cu.

could be taken to mean that they cross down through the twos, but the fact that they finish in the twos' place makes it clear that it's cross and cast. It seems obvious from the timing that go the Figure

is a half figure eight rather than a full one. Playford doesn't give the symbol for the end of B1 but we know where this should be. And surely the final and cast off

is just part of the half figure eight; they wouldn't finish the half figure eight and then cast off to finish below the threes.

But now the usual dilemma — will anybody want to dance it? It's a triple minor where the threes do absolutely nothing — we only know they exist because the ones do a half figure eight through them. We could convert it to a three-couple dance — but the threes would still do nothing except move up to become twos! Better to convert it to duple minor and point out to the bottom ones that they need to do the half figure eight down through an imaginary couple. But should we add in extra moves for the twos? Usually I avoid that, but this time I'm giving in to the temptation! It was all about the ones in Henry Playford's day, but now other people want to keep moving. Certainly at the end of A2 we can have the twos doing a back-to-back at the same time as the ones. What about converting “half figure eight” into “half double figure eight”? There are three of them, and we can't convert all three or the twos would end improper. In fact “Ones cross, cast and half figure eight up” is such a standard move that I wouldn't want to mess with it. But we could certainly convert the matching pair of half figure eights in B2 to half double figure eights. This is the point where you get to dance with a new couple, so I would stress both when walking it through and when calling the dance, face the next couple. And then tell the twos that they don't need to cast up into it, as some people insist on doing — they're already facing up, so they just move up the outside as the ones cross down through them. Similarly when they finish the first half double figure eight by crossing down through the ones they stay facing down and start the second half double figure eight by moving down the outside while their original ones cross up through them. Again if there's a couple missing at the end the twos need to do it with an imaginary couple.

And I need to talk about the music. The version Playford gives has so many short notes that it's virtually unplayable! I imagine some virtuoso flautist or recorder player embellished the original tune with lots of grace notes and presented that as the correct version, so it's here for any virtuosos and musicologists, but for ordinary musicians I've put it back to what I imagine was the original version of the tune — take your pick!

Arundel Street

Format: Longways duple minor Improper| A1: | Men back-to-back on the diagonal. Ladies back-to-back on the diagonal. |

| A2: | Back-to-back neighbour. Back-to-back partner. |

| B1: | Ones cross and cast; twos lead up. Ones half figure eight up through twos and all face the next couple. |

| B2: | Half double figure eight with this new couple, started by the ones crossing down through their new twos (who would have been threes in the original triple minor dance) as the twos move up the outside. Half double figure eight with your original couple, started by the ones crossing up through the twos as the twos move down the outside, finishing with the twos crossing up through the ones ready for the new men to start again with the back-to-back. At each end of the set, couples out of a half double figure eight must do the move with a ghost couple or just cross over. |

Barham Down

Source: Dancing Master 11th Edition 1701: Henry Playford.Format: Longways triple minor

First cu. cast off into the 2. cu. places, then Arms round with both Arms, the same back again : First cu. cross over into the 2. cu. places, then go the half Figure, then 1. cu. lead down abreast with the 3d. cu the first man goes round the 3d man, the 1st wo. the same with the 3d. wo. at the same time into the 2. cu. places :

The facsimile is from John Young's 17th Edition of 1721, but I've given Henry Playford's wording in the 12th Edition of 1703 which is almost identical, with an identical tune. See this here on page 297 but you need to go to page 309 because the PDF has several pages before Playford's page 1.

The music is in triple time, with two sections each 4 bars long, and in the 12th Edition the underlined dots are both double, presumably meaning two A's and two B's without saying where to split them though that seems clear enough. The 17th Edition has three dots after the B section, but I think that's a mistake.

It's a dance for the ones: the twos move up, move down, move up, and the threes lead down and presumably move up. I don't blame interpreters for making it a more equal dance. I'd be inclined to do the half figure eight down through the threes rather than up through the twos, but who knows? And there's that strange phrase Arms round with both Arms

rather than “turn two hands” if that's what it means. But I don't need to interpret the dance: there are already at least three versions.

Tom Cook has a rather complicated duple minor version which you can see here. A. Simons (the “Kentish Hops” man) has a triple minor version which you can see here.

Here's yet another version:

Barham Down

Interpretation: Daisy Black, 2019.

Interpretation: Daisy Black, 2019.Format: Longways duple minor

| A1: | (4 bars): Ones cast, twos lead up, ones (or both couples) two-hand turn. |

| A2: | Twos the same (home). |

| B1: | (4): Ones cross, go below twos who lead up (6 steps); ones half figure eight up, meet in the middle of a line of four. |

| B2: | Lead up in line three steps, fall back; ones assisted cast. |

Daisy's preference is for both couples to do both two-hand turns, and she's in good company — Pat Shaw does the same in his interpretation of Holborn March — but as in that dance, each couple doing one turn is closer to the original.

The Barley Mow

Added 24-Jun-25

Added 24-Jun-25

Source: Twenty four Country Dances for the year 1779: Thompson.Format: Longways triple minor.

Original wording: (Or see the whole book)

Hands round 3 with the 2d. Wo.the same with the 2d. Man

Cross over & half figure

lead thro' the bottom and cast up

Hands 3 round Man at bottom & the Wo. at top at the same time

Hey the same

hands six half round & back again

Allemand half round & back again

This one appears in The Apted Book, though they've substituted “Linnen Hall” for the original tune. In the Preface the editors say,

Actual alteration of the figures has been avoided as far as possible, but in several cases the original instructions have been expanded and supplemented, as will be seen from the notes appended to each dance.

And yet they've left out the half figure eight up, left out the final allemandes, and cut the dance down to 32 bars, i.e. once through the tune, which involves a hey for three in only 4 bars. The dot symbols show that once through the dance needs twice through the tune, as with The Fandango and others. It's easy to say “Well, that's obviously wrong” and hack it about to make it fit once through the tune, but Andrew Swaine stresses that an interpreter must first make a real effort to determine whether the original instructions could actually be correct.

The tune is a jig with A and B sections 8 bars each. [There are actually several tunes called “The Barley Mow”.] How could a circle of three people be padded out to 8 bars? Surely by circling left and right. The same with A2. For B1 we have ones cross, cast and half figure eight up which is certainly 8 bars. But B2 is ones lead down one place and cast up which would be very slow for 8 bars — let's leave that for the moment. A3 is circles of three (as is A1), so again circle left and right. A4 is a hey in the same threes, cut slightly short so that the ones finish in middle place on their own side. B3 is all six circle left and right, and B4 is two allemandes, though there's time to allemande once around in each direction rather than the half-way specified.

So that leaves us with the problem that there's too much music for the ones to lead down and cast up. I suggest that Thompson has missed out something for the ones before or after casting up, so I'm adding a two-hand turn. Of course I can't prove it, and you may say I'm just as guilty of changing the dance as the editors of the Apted Book, but at least I'm giving you my reasoning.

As with many triple minors, I would convert this to a set dance for three couples by making a small change in the last four bars, though actually the threes do a lot more in this dance than in most triple minors of the period. Anyway, here's my version.

The Barley Mow

Format: 3 couples longways.Interpretation: Colin Hume, 2025.

Music: 6 x Own tune.

| A1: | Ones and second woman circle left. Circle right. |

| A2: | Ones and second man circle left. Circle right. |

| B1: | Ones cross and cast; twos lead up. Ones half figure eight up, finishing proper in second place. |

| B2: | Ones two-hand turn. Ones lead down through threes and cast up to second place. |

| A3: | Man down, woman up (i.e. ones to own right): circle left with this couple. Circle right. |

| A4: | Hey across with the same couple: ones go through the gap and turn left to start, finishing in middle place on own side. |

| B3: | All circle left (slip-step). Circle right. |

| B4: | All allemande right. Ones cast to the bottom as the others allemande left, threes moving up. |

The Bath Waltz

Skip to instructionsI learnt a version of this from Valerie Webster and have called it many times since 2008. It's been cleverly converted from triple minor to a 3 couple set, and it's accessible: I've called it three times at a Jane Austen evening arranged by The Round in Cambridge where there were lots of young women in beautiful dresses who wanted to be Elizabeth Bennett but knew nothing about dancing. However in 2023 I decided I really wanted to look at the original wording — and this turned out to be more difficult than I expected! When I looked on RegencyDances.Org I found two versions, here and here. The first is from William Campbell's “20th Book of New and Favorite Country Dances & Strathspey Reels” from around 1805 — but it's a different tune and dance! How can this be? Well, very easily. Bath was the fashionable place to dance in Regency England, so if you were a publisher hoping to sell lots of copies of your book it's an obvious title to choose. The second is from a later book — Charles Wheatstone and Augustus Voigt's “A Selection of Elegant & Fashionable Country Dances, Reels, Waltz's &c. Book 9” from 1814 — this is a version of the tune I had, but the figure bears no resemblance. And I had believed that the dance and tune had been published by Cahusac in 1798, three years before he published “Duke of Kent's Waltz”. There's also a dance of that name in the Preston 1799 collection but that's another tune and figure.

So I asked Paul Cooper, the Regency expert who does most of the interpretations and animations for the site. He sent me a copy of the Cahusac which turned out to be yet another tune and dance bearing no resemblance to what I was looking for! He then added,

That said, your tune is included in a later Cahusac publication named 'The German Flute Preceptor' from around 1815. So there is a genuine Cahusac source, and an assumption might have been made that the 1798 and c.1815 tunes would be the same just because the names are the same. Wilson published the same tune in his 1816 'Companion to the Ballroom'… and looking at his figures, that's what you have! You have an arrangement of Wilson's first suggested figures for 'Prussian or Bath Waltz'.

WALTZ FIGURE Each strain repeatedChain figure 6 round with progressive waltz step

waltz whole poussette with sauteuse step

& swing corners a la waltz

OR THUS

The 3 ladies turn their partners a la waltz

promenade 3 Cu: with progressive waltz step

swing with right hands round the 2d. Cu: & chain figure 4 round at bottom with progressive waltz step

Again some people would say “But how can there be two figures to the same dance?” because they've been led to believe that every dance has one tune and one figure. This was probably true in John Playford's day, but 150 years later it certainly wasn't. You can read Wilson's book at google.co.uk/books/edition/

The time of each Tune has been carefully marked against it, in order to render the Dance uniformly complete, and the Figures are written to correspond exactly; and, with a view to render the Work as correct as possible, each figure is written expressly for this Work, calculated equally to suit the Learner and the most experienced Dancer…Accordingly, three Figures are generally given to each — the first easy; the second more difficult; and the third for the most part double.

“double” generally means each part of the tune is repeated, whereas “single” generally means without repeats. So I think we must accept what Wilson says. He has made up two or three sets of figures for each tune and the combination of this tune and figure has never appeared anywhere before. Indeed on page vii he says,

… those who wish for a greater variety of Figures, may consult the Tables in the “Analysis of Country Dancing,” invented for the purpose of enabling Dancers to set their own Figures to any Extent.

This reminds me of Mozart, who (allegedly) produced a mix and match method for writing your own minuets by throwing a dice to select chunks of music from each column in turn.

Wilson finishes his preface:

All the Airs in this Collection are original, and such as have received general applause. Every attention has been paid to rendering them correct; and the Author trusts that this Work, when closely examined, will be found the most perfect of any thing of the kind hitherto attempted, and that it cannot fail to be rewarded with universal Approbation.

So what do we make of Wilson's first figure? I don't know what he means by progressive waltz step

unless he means moving steadily forwards rather than rotating. Chain figure 6 round

is surely what I would call a grand chain, where the ones start giving right hands to partner and the twos and threes give right hands to neighbour. But taking two waltz steps per change still only adds up to 12 bars, and the music has 16 bars.

waltz whole poussette with sauteuse step

isn't obvious either. whole poussette

actually means one and a half because the ones need to finish in second place ready for the “swing corners” figure. And what is a sauteuse step? According to Susan de Guardiola,

For the sauteuse waltz: the sauteuse step as described by Thomas Wilson, that being the closest description available. Leap-slide-close, leap-run-run.

That sounds far too energetic for me!

Paul Cooper has written a paper on The Works of Thomas Wilson, Dancing Master.

You can read the whole of Thomas Wilson's “The complete system of English country dancing containing all the figures ever used in English country dancing, with a variety of new figures, and new reels” (c. 1815) on the Library of Congress website.

You can read Wilson's “An analysis of country dancing” on the same site. Or if you want the full title: “An analysis of country dancing wherein are displayed all the figures ever used in country dances, in a way so easy and familiar, that persons of the meanest capacity may in a short time acquire (without the aid of a master) a complete knowledge of that rational and polite amusement. To which are added, instructions for dancing some entire new reels; together with the rules, regulations, and complete etiquette of the ball room”. But I don't know where Wilson describes “sauteuse step” or “progressive waltz step”.

At gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/

Paul Cooper says:

Wilson's terminology for waltz country dances is open to interpretation. He announced (in various advertisements and publications) that he'd invented the concept of “waltz country dancing” in 1815. He didn't invent the concept of country dancing in Waltz time of course, that had been popular since 1790 or so. What he'd invented was this new terminology involving Sauteuse steps and 'a-la-waltz' variations of figures. He also advertised that he was working on a book to explain it all. His 1816 “Correct Method of Waltzing” has “Part 1” written on the cover. Part 2 was perhaps (I'm guessing) intended to be his volume on Waltz Country Dancing in which he'd have answered all our questions. It seems never to have been published so guess work is required. He included examples of his waltz country dances in all of his dance collections from 1815 forwards; they're an interesting sub-genre of late Regency country dancing. But interpreting his meaning is an exercise for the reader. I imagine that he must have been teaching something moderately unusual/new; the industry would have laughed at him if all he'd done was claim credit for what everyone had been dancing for the past 25 years. So slightly fanciful arrangements of the figures makes sense to me.My current guess on the pousette is that some kind of waltz turns would be injected into them. Perhaps adopting a waltz embrace with your partner, then waltzing around the neighbouring couple; perhaps doing so as many times as uses up the music. Just a guess, I've nothing to base that on except the guess that it's something other than a regular pousette.

This is an area which is still being explored, and I'm not the expert to do so — I'll just give one example. See efdss.org/vwml-digitised-

Le Sylph — An elegant collection of Twenty four Country Dances, the figures by Mr. Wilson. For the year 1818 Adapted for the German Flute, Violin, Flageolet or Oboe.

For many of the dances, such as “The New Tyrolese Waltz” and “Twoli”, there are two figures. The first is a Waltz figure

, the second is a Country Dance figure

and they take the same amount of music. Looking at the first of these dances, I can see how the Country Dance figure fits 32 bars of waltz time, but I've no idea how the start of the Waltz figure, The 3 Ladies & 3 Gent:set to each other

can fill up 16 bars. I'm not even going to guess; I'll leave that to the real scholars.

Moving on from all that, here's Wilson's description of Whole pousette (as he spells it) from “The complete system of English country dancing containing all the figures ever used in English country dancing, with a variety of new figures, and new reels”.

The top couple at A join hands and move in the line a a a, while the second couple B join hands and move in the line b b b, by which means they move round each other twice and change situations, the couple B will have moved to A, and the couple A will then take the place of the couple at B, which finishes the Figure.

From the diagram you can see that the movement is anti-clockwise, i.e. first man pull, second man push, and it's 1½ rather than twice. There's no mention of rotating, so it seems to be a regular push-pull poussette — but how can you pad it out to 16 bars?

Some time after writing this I went to a workshop with Anne Daye in which she said that a poussette in Regency days was a rotating move, much like a “swing and change” in English Folk dancing — though that's a move which seems to be little known now. Paul Cooper has an article on The Pousette Figure in English Regency Dancing in which he says,

Wilson's figure was similar to a that of a regular rotational pousette except that the couples rotate one-and-a-half times in order to change places.

and later,

The Waltz dance entered the English ballrooms from the start of the 19th Century, it triggered the invention of something named the Waltz Pousette. Thomas Wilson, for example, used this figure in his 1818 Le Sylphe dance collection. He employed such phrases as “whole poussette with sauteuse step” and “waltz whole poussette”. This appears to be a turning pousette, it could be the origin of the pousette figure used in RSCDS Scottish Country Dancing.

I haven't tried to add in that factor — and I still don't see how it could use up 16 bars.

The final figure is swing corners a la waltz

. Does a la waltz

just mean “using a waltz step”, and is that different from a progressive waltz step? I don't know, but at least I can find Wilson's description of “swing corners” on page 64 (Image 89):

The Gentleman at B swings the Lady at A with his right hand and moves to C, while the lady moves to D.The Lady at A swings the Gentleman at C with her left hand, while the Gentleman at B swings the Lady at D with his left hand, then meets his partner at E.

The Gentleman at C swings his partner at A with his right hand and moves to D, while the Lady moves to B.

The lady at A swings the Gentleman at C with her left hand, while the Gentleman at B with his left hand swings the Lady at D, they then then return to their places at E F, which finishes the Figure.

N. B. In performing this Figure the Lady always swings her partner with the right hand, and the top and bottom Gentlemen with the left. The Gentleman likewise swings his partner with the right hand, and the top and bottom Ladies with the left.

I find it very confusing that he keeps changing the letter names between the four figures, but I understand what he's saying. And yes, he does say “then then”.

There are several differences from the tune I picked up from somewhere. You can see the version on page 22 of “The German Flute Preceptor” at imslp.org/wiki/

I was wondering why different publishers printed slightly different versions of the same tune. Paul Cooper explains:

One interesting thing about the early 19th century is that there were an abundance of music shops operating in London, they were competing with each other for much of the same market. If a tune was remotely popular, it was liable to be published many times over. In some cases publishers straight up copied from each other; in others tunes migrated more organically, perhaps with a musical person hearing a tune at a ball and memorising it, then selling it to a music shop the next day from memory (perhaps as Lady so-and-so's favourite). The result being that it's not at all uncommon for minor differences to appear between published tunes, names of tunes, time-signature, and so forth. That all came to an end in the late 1810s when the copyright regime became less permissive, but for roughly 20 years a proliferation of tunes across published sources was common. All of which is a complicated way of saying that I wouldn't be concerned about minor differences between your tune, the Wheatstone version and the Wilson version. They're close enough that they were surely intended (and understood) to be the same.

I contacted Liz Bartlett, leader of the Jane Austen Dancers, who told me that the reconstruction was by the group's founder, Elspeth Reed, and Valerie learnt it at the same time that she did. She confirmed that it was from Wilson's “Companion to the Ball Room” 1816, Figure 1. And althought that calls it “Prussian or Bath Waltz” I'm using Elspeth's title: “The Bath Waltz”.

I asked her how she distinguished between “country dance figures” and “waltz country dance figures” and she replied,

- Country Dances: dances to Reel-time, Jig-time, Waltz-time tunes etc. Even if the tune was waltz time it was still a Country Dance

- Couple Waltzing: enclosed embrace-hold dancing exclusively with your partner entire time — becoming more widely danced in 1810s it was frowned on, so to dilute the amount of time “embracing” (and to gain acceptance for Couple Waltzing in society) they “invented”:

- Waltz Country Dances: dances to Waltz-time tunes but containing waltz moves such as “turn a la waltz” with both partner and corners etc. — so you would in effect be Couple Waltzing but with more than one person and only for a short time before the next move, e.g. lead down and back etc. By his 1816 Companion, he dropped the term, but the Couple Waltzing aspects remained (see Prussian/Bath Waltz 1816). I use it as it's a good way of distinguishing the dances, to see how they got Couple Waltzing through society.

I asked whether the figures explained by Wilson have a different meaning when it's a waltz country dance. She said,

They will be based on the figures everyone knew, but waltz-i-fied. There's no documentation / book I know of explaining “poussette a la waltz”, “waltz with progressive steps” (when applied to Waltz Country Dancing) — I have looked, but it seems you needed to go to class! There was chaos back then too — I've got extant quotes — especially during the Napoleonic Wars when all the Allied countries had their own version of Couple waltzing.

One such quote which always makes her laugh is from Lord Clive's Journal, 1814-1815 (page 89):

In the evening afterwards I went to a dance at the Baron de Gagern's, where they were dancing country dances à l'Anglaise, as like them to be sure as Germany is to England; but, however, I thought myself safe at that sport, or else that my London education had been wholly thrown away, upon which I asked Lady Isabella Fitzgibbon to honor me with dancing a country dance with me. As the devil himself would have it, they introduced a waltz in the middle of the figure, and there I was in a glorious scrape. Luckily Planta, Lord Castlereagh's secretary, knows no more of dancing waltzes than I do, and so I was not single in my blunders. First we attempted to pousset it, that did not suit; we made one attempt at a waltz, and then we went to the bottom of the dance, which I thought a remarkably wise measure. I have made some good resolutions about dancing. I do not know how long I shall keep them, but no more waltzing for me, unless I get some fair instructress first, who is a perfect mistress of the art of waltzing, to give me a few lessons.

She also said,

When I started Regency calling in c2006 we had only a few Waltz Country dances, and I decided to make a study of them alongside couple waltzing etc (pre Internet giving us all the answers!), so if I was interpreting the 1816 dance, now I'd probably interpret it with “rotating as you go poussettes” / waltz arm holds etc. But we like Bath Waltz 1816 as it is, in the same way as Duke of Kent and Mr Bev aren't worth changing.

Naturally I had to point out that I have my own interpretations of both Duke of Kent's Waltz and Mr Beveridge's Maggot!

And then Paul Cooper made an equally clever suggestion for the first move: instead of everyone starting the grand chain, how about making it progressive: the ones start, bring in the twos and threes as they meet them, and keep going till everyone is home. This goes all the way back to “Nonesuch” in Playford's first edition of 1651. But it doesn't tie up with Wilson's description on page 88 (Image 113):

The Lady at A and Gentleman at B, the Ladies at C G, and the gentlemen at D H, swing with the right hands, then they all swing with the left hands, continuing in a direction from right to left, swinging with the right and left hands alternately till they all regain their original situations, which finishes the Figure.

That's really disappointing! Wilson may tell us how perfect his book is, but he doesn't explain the timing, and Paul's suggestion fits the music perfectly.

So my (current) approach is to go with Elspeth's version but add Paul's suggestion for the grand chain. Is it right? I doubt it. Does it work? Certainly! The final move of the grand chain is the threes crossing back to their own place, so the ones and twos can be ready for the poussette. And the final move of the dance is the ones doing a left-hand turn in middle place, which means the new ones are ready to start the grand chain, and the twos and threes don't need to remember which way to face — the ones will bring them in to the chain as they meet them. I called this successfully at The Round at their first meeting in October 2023 with several new dancers, and I look forward to calling it to yet more beautifully dressed young women!

I may return to this topic later, but it's turned out to be much more complicated than I expected, and I need a break from it! I'll leave you with Paul Cooper's paper on The Regency Waltz: regencydances.org/paper013.php

The Bath Waltz

Format: 3 couples longways.Dance: Thomas Wilson: Companion to the Ballroom, 1816

| A1/2: | Ones start a progressive grand chain: change right hand with partner, change left hand with the twos. Everyone change right hand with the next (ones with threes, twos with partner) and keep going till all are home. Use two waltz steps per hand, dancing in a curve rather than just pulling by. |

| B1: | First man push, second man pull: Half poussette at the top. First man pull, third man push: half poussette at the bottom. [It's always the end man who pushes.] |

| B2: | Twice more from new places, finishing 3, 1, 2. |

| C1: | Ones turn first corner right, partner left 1¼. [There is more time than people think for this, so don't rush it.] |

| C2: | Second corner right, partner left 1½. [Reverse progression] |

One final comment: Alan Winston, Regency Dance expert from California says, “It seems like a lot of the [Regency period] waltz-time dances are 48 bars and have 16 bars of ”swing corners“ in them, so they're not very different.”

The Beggar Boy

Added 26-Jan-26

Added 26-Jan-26

Source: Dancing Master 1st Edition, 1651: John PlayfordFormat: Longways duple minor

Leade up all forwards and back .

That againe :First and last on each side to the wall, while the 2. Cu. meet, back all to your places, men hands and goe halfe round, We. doing the like . All that againe : Sides all .

That againe :First and last meet and change places, while the 2. Cu. goes back and meet, first foure hands and goe round, while the other set and turne S. . All this again : Armes all .

That againe :Back all a D. meet againe. half the S. Hey : That againe :

This is basically the same as Cecil Sharp's version.

Sharp has the circles in the first figure going all the way round rather than the halfe round

specified, and I agree with him.

In B2 for the second figure he just says Repeat B1, to places.

but Playford says First 4.hands and go round,while the other set and turn S

so surely this has to be positions rather than numbered couples.

In the third figure, as I say on my page about The Hey, I expect the ones to lead the hey. I see it as a whole Hey interrupted by falling back and coming forward, so the first half starts at the top with the ones and twos passing right shoulder and the second half starts at the bottom with the ones and twos passing left shoulder. I would do the same in Chestnut.

| First Figure: | |

| A: | Up a double and back. That again. |

| B1: | Ends face out and move out a double while twos meet; all fall back. Circle left on own side. |

| B2: | All that again. |

| Second Figure: | |

| A: | Side right shoulder to right. Side left. |

| B1: | Middles fall back a double and move forward, tops lead to the bottom, bottoms move up to the top outside them. Circle left at the top, set and turn single at the bottom. |

| B2: | All that again from new places. |

| Third Figure: | |

| A: | Arm right. Arm left. |

| B1: | Take hands in lines: Fall back a double; lead forward. Twos face up: half a straight hey starting right shoulder. |

| B2: | Lines fall back a double; lead forward. Twos face down, pass left shoulder: half a hey. |

Bobbing Joe

Source: Dancing Master 1st Edition, 1651: John Playford.Interpretation: Colin Hume, 2013.

Format: Longways duple minor

Leade up forwards and back . That againe : Set and turn S. . That againe : First Cu. slippe down between the 2. they slipping up . then they slippe downe . hands and go round : The first two men snap their fingers and change places . Your We. as much : Doe these two changes to the last, the rest following. Sides all . That againe : Set and turn S. . That againe : First two on each side, hands and go back, meet againe . Cast off and come to your places : First foure change places with your owne . Hands and goe halfe round : These changes to the last. Armes all . That againe : Set and turn Single . That againe : Men back a D. meet againe . We. as much : First Cu. change with the 2. on the same side . Then change with your owne : These changes to the last.

The tune is a jig with a 4-bar A and a 4-bar B, presumably both repeated. The dance apparently appeared in all editions of The Dancing Master, though it seems highly unlikely that people would still have been dancing it in 1728 when “Up a double”, “Sides” and “Armes” were ancient history. As I mention in my Connections notes, many of the progressive longways dances from the first edition had the three standard introductions. We hardly ever dance them now, but I was looking for something different to call at my “Playford for Fun” session at Whitby Folk Week in 2013 and picked on this one. Playford lays out the instructions so that it is clear which go with the A-music and which the B. The underlined dots reassure us that there are two A's and two B's except that the line starting First Cu. slippe down between the 2. they slipping up

has two underlined single dots, but let's assume that's a mistake. So the first figure starts in an absolutely standard manner: Up a double and back, that again, set and turn single, that again. The body of the figure starts with a move reminiscent of the “matchboxes” move in the second figure of “Picking of Sticks”: the ones slip down the middle as the twos slip up the outside, then reverse it, and circle left. The second half needs to progress, and it clearly does. Playford refers to “first two” or “first foure” because at that time a progressive longways dance was started by just the first two couples, the others watching and joining in as the original top couple reached them. We might wonder if Doe these two changes to the last

means that the progressive part is just the B part repeated over and over, with these two changes

meaning the men changing places and then the women, but I would like to think that you do the body of the figure with each couple in turn, otherwise the progression would be perfunctory indeed.

But what about the timing? How can we use up 4 bars (8 beats) on The first two men snap their fingers and change places

? Sharp contrives this by having the first man snap on the second beat of bar 1, the second man on the second beat of bar 2, then four steps to change places. But is that really what Playford meant? Let's see what happens in the other two figures. The second figure has cross with partner and circle left half-way, which I would expect to be 8 steps. The third has cross with neighbour and then with partner — again 8 steps. Sharp gets round this by adding some inventive finger snapping at the start of the second figure, but that still means 8 steps for the circle half-way which seems very slow given the liveliness of the dance and tune. In the third figure he adds finger snapping before each half of the move, but who's he kidding? Is it likely that John Playford left all this out? I know Playford is very concise — Sharp takes three pages to explain the dance — but I don't believe he would have left out so much. Surely a more likely explanation is that the underlined dots are wrong, and there is only one B.

One other point worth mentioning is that the final figure leaves everyone improper. I'm assuming throughout the dance that the instructions refer to both couples; I think it was later that the instructions were by default addressed to the first couple. So the second figure is “cast and lead, lead and cast” rather than just the ones casting and leading back up. Similarly I believe Then change with your owne

in the last figure is addressed to the twos as well. So if we've just danced the first turn of the final figure, the original top couple are now progressed and improper when the figure starts again with Men back a D

I'm guessing that the first man would take the instruction as referring to him, though since he's improper he would be taking hands with the next woman and falling back with her. I may yet change my mind about this! For modern use I would start by taking hands four from the top, so everyone except the neutral couples would be improper on alternate turns of the figure. The other concession to modern taste is that I wouldn't run each figure all the way down the set and back. Four or six times through each figure sounds a good compromise, meaning that with an even number of couples everyone will be in at the start of each figure. Of course if there is a neutral couple at the bottom they can join in the three introductions, just as the whole set would have done in 1651 before the top two couples started the body of each figure.

A final thought is that since Playford wrongly indicated two B's in the body of the figure he may well have the same mistake in the introduction, in which case there should be only one “Set and turn single”. I'll assume that, if only to make things easier for the musicians! So I've written the music out with an 8-bar A and a 4-bar B which means the musicians just have to play A B repeatedly, and that's how I've notated the dance in the following instructions.

Bobbing Joe

Format: Longways duple minor| First Figure: | |

| A1: | Up a double and back. That again. |

| B1: | (4 bars): Set and turn single. |

| A2: | “Matchboxes”: Ones give two hands and slip down the middle as the twos slip up the outside; reverse. Circle left. |

| B2: | (4 bars): Men snap their fingers and change places; women the same. [Progression. Do A2 + B2 three more times.] |

| Second Figure: | |

| A1: | Side right. Side left. |

| B1: | Set and turn single. |

| A2: | Take nearer hand with neighbour and fall back; lead forward. Ones cast and lead back to place, twos follow. |

| B2: | (4 bars) All cross right shoulder with partner, turn right; circle left half-way. [Do A2 + B2 three more times.] |

| Third Figure: | |

| A1: | Arm right. Arm left. |

| B1: | Set and turn single. |

| A2: | Men fall back with neighbour; lead forward. Women the same. |

| B2: | (4 bars) Cross with neighbour; cross with partner. [Do A2 + B2 three more times.] |

The Bowmen of Kent

Source: Skillern, 1795Format: Longways triple minor.

Interpretation: Colin Hume, 2023.

Format: 3 couples longways.

Right hands 4 half roundLeft back again

lead down 1 Cu

up again cast off

hands 4 round at bottom

right & left at top

The tune is a lively double jig with an 8-bar A-music and a 4-bar B-music, each repeated. Paul Cooper has interpreted the original triple minor dance at regencydances.

There are one or two oddities to consider. The underlined dots say that there are three sections of music, each repeated, but I assume that the musical notation is correct and that each dot represents four bars. Right hands 4 half round

seems to be an odd mix of “Right hands across half round” and “Hands 4 half round” but I'm assuming the former. I find it fussy to have the stars going half-way, perhaps with setting or falling back to fill up the music, so I'll go for stars all the way round. The rest will work, though it's very busy for the ones going from a circle left all the way to four changes at the top with only two steps per change.

However, in “Kentish Hops” (the book, not one of the leaflets) it has been converted to a 3 couple set which looks undanceable to me. In fact I can't blame Simons for this: the book is a tribute to him, and says:

Collected by A. (Bert) Simons

Produced by Charles Learthart — Orpington Folk Dance Chairman

First of all he has all three couples in the right-hand star and left-hand star — that's not undanceable but it's so wrong that I wouldn't call it — the star would certainly have been for the ones and twos. No objections to the ones leading down, leading up, casting to second place and then circling left with the threes. But in the next four bars (8 walking steps) he has the ones and twos doing four changes plus a fifth change to get the ones to the bottom, and then they have to turn back to become threes in the next right-hand star. So what's the answer? We could have the twos moving up as the ones lead down, then the ones lead up to second place and cast to the bottom as the threes move up, so we're already in progressed positions (2, 3, 1), and then it's circle left at the bottom and four changes at the top. The dancers still have to make sure that the circle left goes all the way round and they're facing the right way for those four changes, but it's possible. It also means the ones aren't involved in the four changes at the top, which is unusual — the expectation is that the ones will be dancing the whole way through the figure. So here's what I think is a better (i.e. less frantic, easier) solution — though I've yet to call it! Of course another possibility is that Skillern missed out the first four bars of the B-music and it should actually be a 32-bar dance!

![]() Click the treble clef and then “Play MP3” (not “Play MIDI”) to download something you can call the dance to: two bars introduction, three times through the tune and a final chord. George Williams has a nice animation of this version at upadouble.info/dance.

Click the treble clef and then “Play MP3” (not “Play MIDI”) to download something you can call the dance to: two bars introduction, three times through the tune and a final chord. George Williams has a nice animation of this version at upadouble.info/dance.

| A1: | Ones and twos right-hand star. Left-hand star. |

| A2: | Ones lead down the middle, turn in. Lead back, cast to second place (twos lead up). |

| B1: | (4 bars): Bottom two couples circle left. |

| B2: | Same two couples, three changes with hands. |

Bulock's Hornpipe

Source: Dancing Master Volume 3, 1726: John Young.Interpretation: Colin Hume, 2009.

Format: Longways triple minor

The first Cu. lead thro' the 2d. Cu. cast up and cast off . The 2d. Cu. do the same : First Cu. cross over and half Figure at top . Then whole Figure with the 3d. Cu. : First Cu. turn all four corners : And then cross over quite round all the 4 corners : Then first Man Heys on his own side and his Partner Heys on hers at the same time . First Cu. leads thro' the 3d. Cu. at bottom and thro' the 2d. Cu. at top and turn his partner :

The instructions say that there are five sections, and the music indeed gives five sections of four bars, each repeated.

I would like to look at this in conjunction with Ravenscroft's Hornpipe, another dance from the same edition:

Note: Each Strain is to be Play'd twice, and the Tune twice through.First cu. lead thro' the 2d. cu. and cast up and cast off . The 2d. cu. do the same : Then first cu. cross over and half Figure a-top with the 2d. Cu . Then whole Figure at the bottom with the 3d cu : Then First man turn the 3d. Wo. with his Right-hand, and his Partner the 2d. Man with hers, and her Partner with her Right . Then first Wo. turns the 3d. Man with her Right, and the first Man turnes the 2d. Wo. with his Right, and his Partner with his Left :

Then the first Man cross over on the outside the 3d. Wo. and his partner cross on the outside of the 2d. Man, and both cast into the 2d. cu. place . Then first Wo. cross over on the outside the 3d. Man. and the first Man cross on the outside of the 2d. Wo, and both cast into the 2d. cu. place : Then the first Man Heys with the 3d. cu. and the 2d. Wo. Heys with the 2d. cu. a-top . Then the Man the same a-top, and the Woman the same at bottom : Then Right-hand and left quite round with the 2d. cu. a-top . Then lead thro' the 3d. and turn your Partner :

The instructions to the two dances are quite similar, but Ravenscroft's is more explicit about the instructions and the timing — it says there are three 4-bar phrases each repeated and the whole tune is then repeated, giving 6 x 8 bars for once through the dance. Bulock's implies that there are five 4-bar phrases each repeated, giving 5 x 8 bars. Both tunes are in triple-time. Ravenscroft's appears in Fallibroome 6.

“Bulock” and “Ravenscroft” are both in italics, indicating that these are men's names.

Bulock's Hornpipe

A1: Ones lead through twos and cast up, then cast as twos lead up (12 steps).

A2: Twos repeat with ones.

I originally had “Twos repeat with threes” but I didn't mean that — thanks to Norman Bearon for pointing it out to me!

B1: Ones cross and cast, twos lead up (6 steps). Ones half figure eight up.

B2: Ones full figure eight down through threes (12 steps).

So far this is identical to Ravenscroft.

C1/2: “First couple turn all four corners” (24 steps). Ravenscroft's has Ones turn first corner right, partner left (in my opinion, though it actually says right), second corner right, partner left. Six steps for each sounds reasonable, and though the ones each turn two corners, together they turn all four corners. Let's go along with that (as Bernard Bentley does).

D1/D2: “And then cross over quite round all the four corners” (24 steps). Ravenscroft's has “Then the first man cross over on the outside the 3d. Wo. and his partner cross on the outside of the 2d. Man, and both cast into the 2d. Cu. place . Then first Wo. cross over on the outside the 3d. Wo. and first Man cross on the outside of the 2d. Man, and both cast into the 2d. Cu. place : ” I suggest these are describing the same figure, and again I go along with Bentley: Ones cross, turn right, man round the third lady and man, lady round the second man and lady, back to second place. Repeat going left, round the other couple. This time each person really does go round all four corners.

Now the two dances differ significantly. Bulock's has: “Then first Man Heys on his own side and his Partner Heys on hers at the same time . The first Cu. leads thro' the 3d. Cu. at bottom and thro' the 2d. Cu. at top and turn his partner : ”

Hey on the side can be done in twelve steps, though you need to start with the ones going down through the threes to make the following move feasible. I believed that Lead down, cast up, lead up, cast down could be done in twelve steps, but when we tried it the dancers thought otherwise — and there's no time for a turn. In fact I think there's a number of dances which glibly throw “and turn” at the end of a set of moves which doesn't allow any time for a turn. So what do we do? The usual answer is to leave out the turn, but if we compare with Ravenscroft's we see that the lead up and cast doesn't appear there, so next time I try it I'll leave that out instead.

As with many triple minors, the threes don't do much, so to my mind it's better danced now as a three couple longways. The only change needed is that the ones turn to the bottom as the threes move up or cast up.

Bulock's Hornpipe

Format: 3 couples longwaysEach paragraph is four bars of 3-time: 12 steps.

| A1: | Ones lead through twos and cast up, then cast as twos lead up. |

| A2: | Twos repeat with ones. |

| B1: | Ones cross and cast, twos lead up. Half figure eight up. |

| B2: | Ones full figure eight down through threes. |

| C1: | Ones turn first corner right hand, partner left. |

| C2: | Ones turn second corner right hand, partner left. |

| D1: | Ones cross left, turn right, round this couple and back to second place. |

| D2: | Ones cross right, turn left, round the other couple and back to second place. |

| E1: | Ones down through threes: symmetrical reels of three up and down. (Morris hey except ends don't cast at start) |